Speeches and Spring Rolls: Global Education Day at Groton

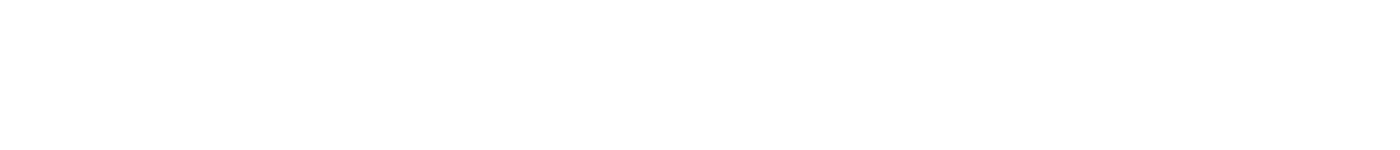

Cambodian human-rights activist Loung Ung visits Groton.

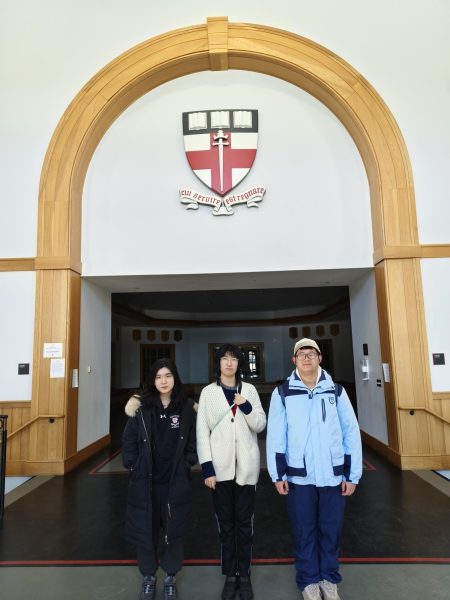

On Tuesday, October 15th, Groton celebrated its second annual Global Education Day. The first day (in the 2014 to 2015 school year), was originally created as a way to promote cultural awareness and expose students to the opportunities for travel and service available to them.

The day began with a chapel talk by Loung Ung, a Cambodian activist for human and women’s rights and the national spokesperson for the Campaign for a Landmine Free World.

Later at lunch, the Dining Hall staff prepared and served food from four different geographical regions: South American empanadas with rice and beans, Asian pad thai and spring rolls, Roman gnocchi, and African peri-peri chicken. In the Webb Marshall Room, desserts were served while Groton students manned information booths about Groton’s Global Education opportunities.

Aidan Reilly ‘18, having gone on a trip to Ollantaytambo in Peru last summer, sat by the South American booth. He said of his experience, “I thought it was a great way to connect with Groton students even though we were so far away from campus.

“Do the work that makes your heartstrings vibrate, ” Ung said to a group of students last week in the Forum. In addition to her humanitarian work, Ung was a writer for the documentary “Girl Rising,” where she told the story of Sokha, an orphaned girl from Cambodia who picked through trash to survive but retained and pursued her passion for dance. She has written two memoirs, entitled “First They Killed My Father: A Daughter of Cambodia Remembers” and “Lucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left Behind.”

In her chapel talk, Ung told her story: her journey from Cambodia to Vermont, from refugee to activist. Her love of Cambodia was evident in her talk, as she spoke of the nation “the size of Oklahoma.”

She spoke of her brothers, who dressed in bell-bottomed jeans to mimic Elvis Presley and of going to movie theaters with her family, all nine of them in a row.

“We didn’t have cup holders in Cambodia,” she joked, remembering using her father as a chair and his hands as holders when she got tired of holding her food. When she fought with her sisters, her father would threaten to replace them with monkeys.

As a child, she was protected from the impending danger around her, “My parents were so loving that they sheltered me from the encroaching bombing.” In 1975, soldiers of the communist group, the Khmer Rouge, arrived in Phnom Penh, where she lived as a child, and evacuated the two million occupants in seventy-two hours. The communists burned their clothes, “the things that made us individuals,” and forced them to wear only black shirts and pants. “I was six when I learned that to survive I had to become dumb, deaf, mute, blind, invisible. How would you silence your voice?”

She was six years old when the soldiers came for her father; she never saw him again. She spoke about that night, “The gods had painted the sky that evening this pallet of gold, magenta, red, and pink. It was so beautiful that I thought for a moment there was possibly a heaven somewhere in our world. And yet there was only hell and hurt and hate in my heart.”

Three months after she learned her father had been executed, Ung’s mother sent her and her siblings away in hope that they would survive better apart. She was taken in by an orphanage who trained her to be a child soldier. “They told me only more of hate. They put a gun in my hands half my body’s height and a third my body’s weight and taught me to shoot and to kill.”

In 1980, Ung, along with her brother and sister-in-law, were sponsored to leave their Vietnamese refugee camp and live in Vermont. She talked about her work with people maimed by landmines, how a little money can provide a limb for a person and thus give them back their life.

A sum insubstantial to some can give a child the ability to walk again, to not need a wheelchair. She ended her talk with a final observation: “The best of man’s humanity is in all of us. We only have to choose it.”

Ung later gave two talks later in the forum, where she talked more about her work in human rights. She spoke about the PTSD she has experienced whenever she is hungry. Hunger brings her back to the years of starvation she experienced as a child, flashbacks to the war that ravaged the beautiful country she called home.

When asked about her return to Cambodia, twenty-five years after her arrival in Vermont, she spoke about the difficulties about the visit. Seeing the harm that the war had left in the country was emotionally difficult for her. There are over twentythousand mass graves in Cambodia. How does a country rebuild itself after so much devastation?

“It is not enough to want to help; you must choose to be of service,” she said. “You must use your authentic voice.”

Today, in the U.S there are over one million charitable organizations in the United States, ranging from big too small. A million ways to help, even in little ways. A million ways to make your heartstrings vibrate.