If you were to ask a waiter, a soldier, and a pastor how they each define “service,” you’d likely receive a discordant array of responses, despite it being a tenet central to all three occupations. In the absence of a coherent definition, the meaning of service has been convulsed among America’s cultural values, replaced by a vague connotation of duty and benevolence. Seizing upon this void, institutions and individuals alike have employed the term to justify their agendas and inflate public appeal.

If you were to ask a waiter, a soldier, and a pastor how they each define “service,” you’d likely receive a discordant array of responses, despite it being a tenet central to all three occupations. In the absence of a coherent definition, the meaning of service has been convulsed among America’s cultural values, replaced by a vague connotation of duty and benevolence. Seizing upon this void, institutions and individuals alike have employed the term to justify their agendas and inflate public appeal.

On January 6, for instance, the insurrectionists that ransacked the Capitol felt that they were doing so righteously in the name of service to their country and ideology. In the same building, though, cowering under their desks only a few feet away, the representatives who voted to certify the 2020 Election results certainly viewed their own actions through the same rationale. With a recent Gallup poll reporting that only 20 percent of Americans are content with the “moral and ethical climate” of the nation, it is time for “service” to be relegated to the archive of trite cultural buzzwords and political epithets which have lost their genuine intent—if they ever had any in the first place. Such words have clouded the nature of public discourse and provided a mask for malevolent causes to conceal their true intentions with.

Groton School has nonetheless stood proudly by the word, vigilantly plastering Cui Servire est Regnare across an impressive range of surfaces. However, when examining the legacy of Groton’s contributions to society, there is little consistency in whom or what Grotonians serve. The Grotonians of the Peabody days, many of whom are decorated today for their commitment to service, all sought to benefit society through definite paths, such as military service and elected office. The Reverend Peabody, who famously precautioned his pupils not to “think too much,” espoused a rigid ideology which emphasized spiritual and public duty. The list of those who were under his tutelage includes the likes of Norman Prince 1905 and McGeorge Bundy ’36. An unwavering proponent of moral education and a skeptic of the unprecedented accumulation of Gilded Age wealth, he once lambasted J.P. Morgan (a Groton benefactor at the time) for his “profitably ambiguous” role in the 1895 Gold Crisis.

More recent graduate data reveals that the most popular destinations for today’s Groton graduates include Goldman Sachs and Sullivan & Cromwell—a multinational law firm that boasts nearly $2 billion in annual revenue. Contemporarily, it seems that Groton has been immensely successful in meeting the regnare portion of its motto. Our graduates dominate the high places in society and exercise a striking degree of influence. The servire component, however, has gone overlooked. As Andrew Greene ’78 inquired in a 2009 Quarterly article, “Whom are we serving when we serve the monopoly?”

Despite its omnipresence on campus, there is one place from which “service” has vanished. On the school website, a few sentences acknowledge that the Community Service program was quietly rebranded as Groton Community Engagement in the 2010s—a move intended to promote a more egalitarian approach to charitable efforts (though the page still advertises that the program will prepare students for a “life of service”). This sentiment, which criticizes the savior-minded approach to philanthropy, is not new. For decades, it has been expressed in discussions surrounding class, race, charity and government. All of which have concluded that the hubris of the savior mindset is profoundly antithetical to “service” since it condescends one party and exacerbates social divisions.

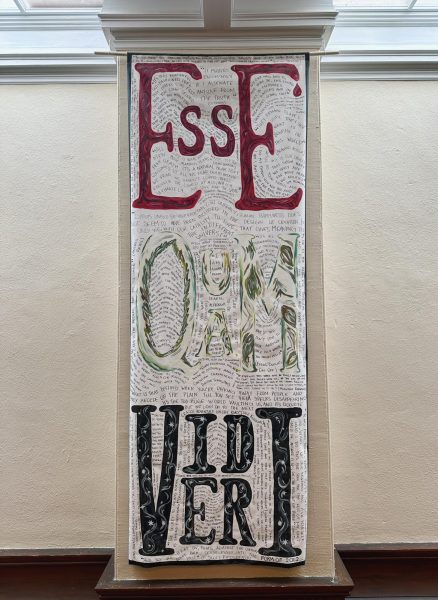

Perhaps it is time to jump ship from Servire and return to an older Groton motto: Esse Quam Videri (“To be rather than to seem”). This phrase stands in stark opposition to the performative action and arrogant attitudes which have come to distort the concept of “service.” Instead of promoting an ambiguous and inconsistent ideal, it encourages a sincerity which is lacking from America’s ethos and is applicable to a wide variety of contexts.