Honoring MLK Day

Every year, Martin Luther King Jr. and his rich legacy are celebrated at Groton with a weekend of activities that reflect his vision of social justice and equality. This year, community workshops, a keynote address from a distinguished speaker on social justice, and a one-act play on racial biases immersed Groton students fully in the ideals and beliefs that Dr. King promoted.

The weekend began with a performance of Shirley Lauro’s play Open Admissions, performed by Director of Theater Laurie Sales and Michael Aduboffour ’17. On a base level, the show concerns a conflict between an overworked professor and a black student who doesn’t think he is receiving the education he deserves. Further, though, the play speaks to the inherent biases of modern American society.

Through the play, Michael, who acted as college student Calvin Jefferson, wanted to show his audience that covert racism and internal bias is a legitimate form of racism: “…you don’t have to be a member of the KKK; you can be racist without realizing it.” His debut on a Groton stage was a tremendous success, inspiring many audience members to reflect on their concept of racism. While he has never “had this particular experience,” Michael connects with his character on stage. “Just because I’m black and because of the way I talk,” he says, “people assume that I don’t do well in the classroom.” The play brought these prejudiced assumptions to life, and effectively sparked a weekend of discussion and reflection.

On Monday, January 16, the community welcomed Carlotta Walls LaNier to the Circle. Mrs. LaNier was the youngest member of the Little Rock Nine, the African-American students who desegregated Central High School in Little Rock in 1957. Inspired by Rosa Parks, Mrs. LaNier desired to get the best education available and enrolled in school as a sophomore.

Ms. LaNier delivered a powerful message about freedom, equality, and the responsibility that all citizens have to make the world a better place. “No person is completely free,” said LaNier, “unless we all are completely free, unless we all have equal access to schools, parks, stores, to churches.”

LaNier discussed meeting Dr. King when he was a young minister and just beginning to emerge as a civil rights figure. She said she met him out of a “sense of duty,” and that when he spoke then, he didn’t yet have the skill of an accomplished orator. Her most enduring memory, she recalled, is of him eating barbecue ribs and drinking a beer. Though some think that such an image diminishes Dr. King, LaNier thinks otherwise: “Sometimes we want our heroes to seem superhuman… but he was like us, a son, a father, a husband, a human being with thoughts and weakness.” By viewing leaders and heroes as real people, she argues, the community has fewer excuses to remain passive. “We all have gifts and talents,” she said, “and we have to ask ourselves, how are we using them? Dr. King wasn’t a superhuman; he was just a man who put his gifts to work for the good of mankind. He would remind us that we all have a gift to share and a role in creating the kind of society that we desire.”

Through a vivid account of her experiences as a black student in a majority white school, Ms. LaNier helped the audience to understand the difficulties she faced and the hopes she held. Many people have asked her why she stayed at Central High School, to which Ms. LaNier replies that she would never think to leave: “The harder the segregation was to keep me out and make my life miserable, the more determined I became to stay and get that degree. Even at fourteen years of age I knew I was on the right side of justice.” Though some students and teachers, she said, were helpful, most scorned her presence in what they thought of as “their” school, and would strive everyday to make her realize that she did not belong. She said that when she went to bed before her first day of high school, “[she] slept the last night of innocence of my life.” Reflecting on these years in high school, LaNier marvels at her parents’ strength, faith, and courage in letting her remain in school. They put everything on the line, including their jobs, because they knew that Ms. LaNier had “as much right as white students to be in school.”

At the end of her presentation, Ms. LaNier urged the audience to engage in dialogue about racism in a nonconfrontational way.“Retaliation,” she said, “doesn’t get you anywhere.”

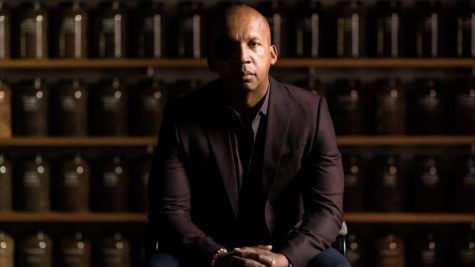

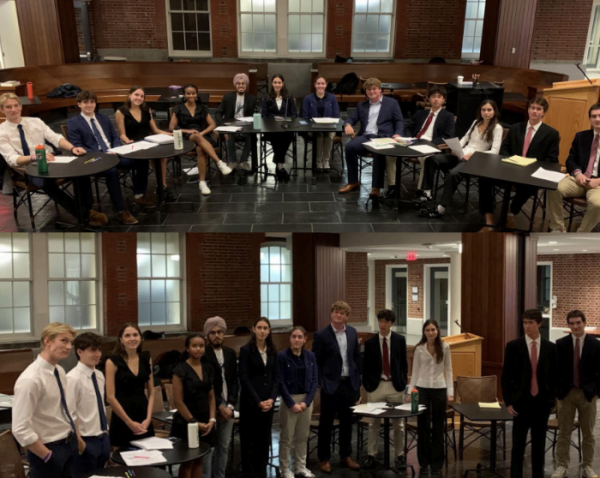

In the afternoon, the Groton community participated in discussion groups that centered around Bryan Stevenson’s TED talk. In the talk, Stevenson, a lawyer and social justice activist, revealed hard truths about America’s disproportionate incarceration rate of minorities and the manner in which race and wealth skew the concept of equal protection under the law. Diversity and Inclusion Prefect Carly Bowman ’17 said that the discussions addressed many issues that the community does not normally talk about. “It was a good way for everyone to get together and share their opinions on a wide range of issues,” she said.

Participants in the discussions felt similarly. Julien Alam ’19 said, “I definitely feel that I learned something about everyone in my group. It was interesting to learn about both our shared history as a country and each other’s personal histories and how they influenced us.”

Reflecting upon the weekend, Head of Diversity and Inclusion Sravani Sen-Das noted, “We heard what our community and the world needs to hear right now.” Perhaps more important than education, though, is action. The events of the weekend made individuals stop and ask themselves what difference they might be able to make. And even the smallest actions matter – in the words of Ms. Lanier, “sometimes you have no idea how many lives you might touch, the different you might make, or the history you might change.”