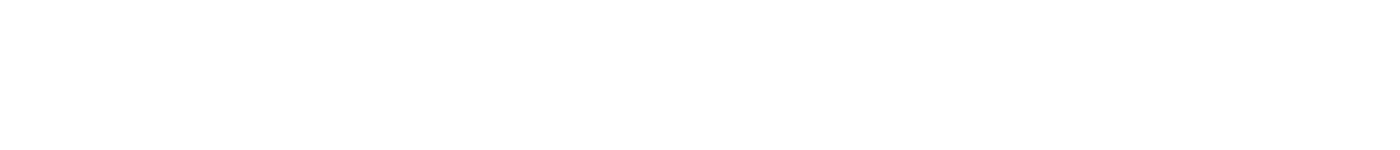

Dear Groton

A People’s Response To The Anonymous Letter

The anonymous letter appeared on the walls of the Schoolhouse.

“If we can be more mindful, more honest, and more empathetic as a community for just a single day, then We’d consider this message a success.”

On the morning of January 12th, students and faculty members walked into the Schoolhouse after chapel to find that an anonymous letter containing this line had been distributed throughout the building. In equivocal terms, the letter writer expressed his discomfort with the Groton School administration’s regulations and authoritative measures and his hopes for fair treatment in disciplinary action, regardless of who the offender happens be.

The letter writer also alluded to tensions that have been built up between certain groups in the student body. The general reaction of the Groton community was one of confusion, mostly due to the vagueness of the wording. Most letters were discarded or torn down, and some were even scribbled on. When asked, the anonymous writer explained that the letter was “an outcry of frustration and misunderstanding” and “a message for the community as a whole to change.”

The fact is that the letter’s message split the school in half, polarizing the population into two opposing factions: some who favored the letters and others who did not. Therein lies its greatest flaw. In a time more than any other, when our community must come together, this letter created a schism and a divide, an “us versus them” mentality for many members of the community that only serves to intensify the anger caused by recent disciplinary actions in Upper School.

That being said, the letter made valid points, and served to bring awareness to issues otherwise unspoken. The school can not simply impose change topdown, and it is “counterintuitive to silence ‘a perceived majority’ in order to express a yearning to change.” In this aspect, the letter almost proved its own point when some faculty openly admitted – even took pride in – tearing down the posters.

When compared to the school’s previous response to students tearing down posters and the idea that all should be able to freely express their opinions, does this not raise questions to the method in which we deal with opposing ideals? Nevertheless, the delivery – plastering the walls of the Schoolhouse with hundreds of prints – could hardly have been more obnoxious. Furthermore, when anyone expresses as strong of an opinion as this one – especially one in which the author has clearly put in so much thought and effort – there is no reason to not sign it. Anonymity implies fear of backlash, backlash from others the author should be more than willing to face. There shouldn’t be, and isn’t any room for disciplinary action. Consequently, there is no reason for the author to remain anonymous.

In addition to a lack of coherence and unwarranted exaggeration, the letter “succeeded in exposing a lack of maturity in both the author and the administration,” says Marco McGavick ’17.

Yet while it does acknowledge issues that need solutions, the letter fails to provide any. Yes, change can’t simply be instituted by a new rule or a letter to the school. We can’t be together if we don’t trust each other. To trust, we have to know and understand each other. It has to be a collective effort, starting from the ground up, in which everybody takes part. As Rand Hough ’17 puts it, let’s “care about the opposite gender for the other six days of the week.” Gender relations have regrettably been a longstanding issue for the Fifth Formers. As supposed role models for the school and future prefects, that’s not the example we want to set for underclassmen and future generations. Everybody needs to be a little friendlier, a little more outgoing. It’s as easy as sitting at different tables at dinner, just a friendly passing conversation in the hallway, or maybe a little favor here or there. If we all made a conscious attempt to be nicer, there’s no telling what even the smallest acts of kindness could do. Sometimes just showing other people you care about them is more than enough.

“Men often hate each other because they fear each other; they fear each other because they don’t know each other; they don’t know each other because they cannot communicate; they cannot communicate because they are separated,” stated MLK. Only through community, through friendship can we come together and rise above the issues that have torn the Fifth Form apart since Third Form. Instead, the letter splits us apart, forcing people to choose sides and stubbornly cling to their positions instead of finding a common ground, a solution that can work for everyone.

Part of the process rests on forgiveness, and a willingness to accept that maybe a mistake was made. Although both sides can remain adamant that they – and only they – are right, the truth is more often than not somewhere in the middle. From one angle, there are some things that should never be said: there simply is not good enough reason to use such antagonistic and derogatory language in almost any circumstance. It’s common courtesy and kindness. Indeed, there is no need to senselessly upset others when there are equally effective but far more peaceful methods to get your point across.

However, there is also a very real and present issue with taking the resultant backlash too far. Given that we live together for an overwhelming majority of the year, someone sometime is going to say something that they regret, make a mistake they wish they didn’t. Everyone makes mistakes; we can’t avoid that. But what we can do is look past them, and not define others by actions they regret themselves.

Every little disagreement can and will flare into a major conflict if we keep saying stupid things or making mountains out of molehills. But if we trust each other, if we forgive each other, those are the first – and arguably greatest – steps we will take towards being a more cohesive form.

It’s Fifth Form winter, and we’re all stressed out. But we’re still stuck together, so we can either spend the next year and a half hating each other or trying to make amends and forging friendships that will last long after we have left the Circle. At the end of the day, these same people are the ones who will define our Groton experience. Even more pressing, in eight months we’ll be running the school. What kind of example do we want to be, what precedent do we hope to set? It’s up to us to decide and to carry through. It’s up to us to come together and resolve our differences. It’s in everybody’s best interest.

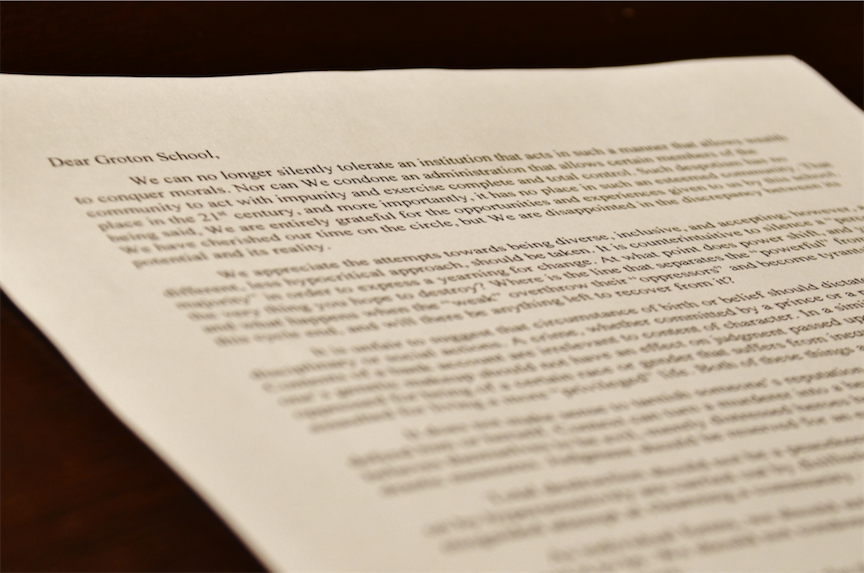

Chris is the Features Editor of The Circle Voice. Having written since Third Form, mostly for the Opinions section, he enjoys telling stories through the...