The Circle’s Lost Legacy

During the sixties, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Boston in April 1965 to lead Boston’s first large-scale march for freedom. Among its nearly 22,000 attendants was an enthusiastic squad of Groton boys who had been bussed from Farmers Row, led by Headmaster John Crocker.

During the sixties, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Boston in April 1965 to lead Boston’s first large-scale march for freedom. Among its nearly 22,000 attendants was an enthusiastic squad of Groton boys who had been bussed from Farmers Row, led by Headmaster John Crocker.

Today, we laud Groton for having been on the right side of history—a side that we see to be morally sound and obvious. Yet, in an era where Americans largely viewed the Civil Rights Movement as a fringe movement, Mr. Crocker had made a daringly radical move on behalf of Groton. In fact, many held a negative perception of Dr. King, per public approval polling from the time. This was not the first time that the Headmaster had pushed a progressive agenda onto the Circle; over a decade prior, and three years before the landmark Brown V. Board of Education decision that integrated American schools, Groton began admitting Black students under Crocker – despite swift and severe backlash from alumni. Similarly, whereas some of our peer boarding schools did not begin admitting girls until as late as 1989, Groton had approved coeducation by 1971. Though Groton’s history is one of trailblazing and moral earnesty, it has shied away from that in favor of avoiding controversy.

Even during the World Wars, Groton’s reaction to international conflict reflects its adherence to a moral standard. During the Great War, as other boarding schools focused on expanding their campuses and continued usual activities, Endicott Peabody redirected Groton’s efforts to supporting the national war effort, such as by growing grain on the Circle and sponsoring military drills for the boys. Rather than sticking to education, the school took a bold stance by supporting the nation’s military despite the popularity of isolationist and neutralist sentiment.

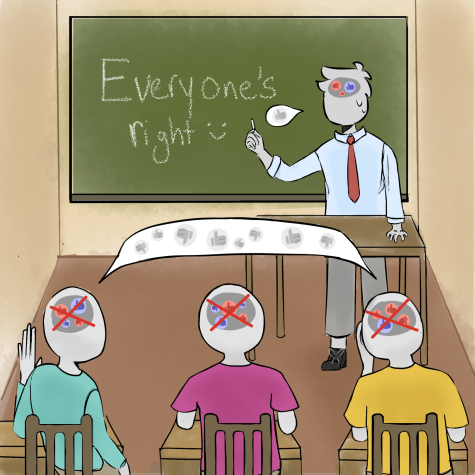

Today, it is difficult to envision Groton sponsoring a move as bold as transporting students to controversial protests. Though our website proudly boasts examples of the school’s avant-garde history, that progressive spirit has largely been subdued in recent decades. In an article recently circulated among several Fourth Form English classes, Deerfield Head of School John N.P Austin encourages educators to practice “Principled Neutrality”—an approach to classroom discussion that fosters productive dialogue without “endorsing a particular program or philosophy.” Of course, Dr. Austin’s analysis is correct—blatantly forcing an agenda upon students will hinder holistic conversations. However, the opposite of the spectrum is not an ideal situation either, in which the scope of discourse is heavily limited in order to prevent discussion on polarizing and potentially uncomfortable topics.Although the school should not necessarily seek to take a single political stance on every matter, it should provide greater opportunity to hear perspectives from across the aisle. When examining Circle Talks from the past decade, few speakers, if any, hold views that strayed from mainstream liberalism. What if Crocker had labeled MLK a radical and kept him off the Circle?

Had Groton abided by a philosophy of principled neutrality through their history, it would never have supported the bold displays of support for the Civil Rights agenda. While Groton proudly touts these instances of political advocacy on its website and pamphlets, our current system of neutrality does not allow us to continue this pattern, and places constraints on the quality and range of discussions. There are several debates occurring on the national stage which Groton could provide perspectives on (such as through engaging speakers), without necessarily taking a stance – gun control, the Supreme Court etc. The desire to avoid disaffecting students with differing perspectives is admirable – and important in maintaining balanced discussions on the Circle. However, it comes at odds with Groton’s outspokenly progressive history. Although we may brag about it, Groton’s trailblazer legacy is on track to become a relic of the past.